The remarkable story of electric clocks begins with Henry Warren. He wanted to make electric clocks, but the current produced by power plants was too irregular. So in 1916 he invented and had installed a master clock to regulate the power - 60hz or cycles in America - by using an old technology, the pendulum driven clock. He could then produce reliable electric clocks with time regulated by a newly reliable electric supply. The synchronous motor was born, and his company, Telechron (meaning time from a distance) was hugely successful. For more of that story and lots of Telechron clocks, I recommend Jim Linz "Electrifying Time".

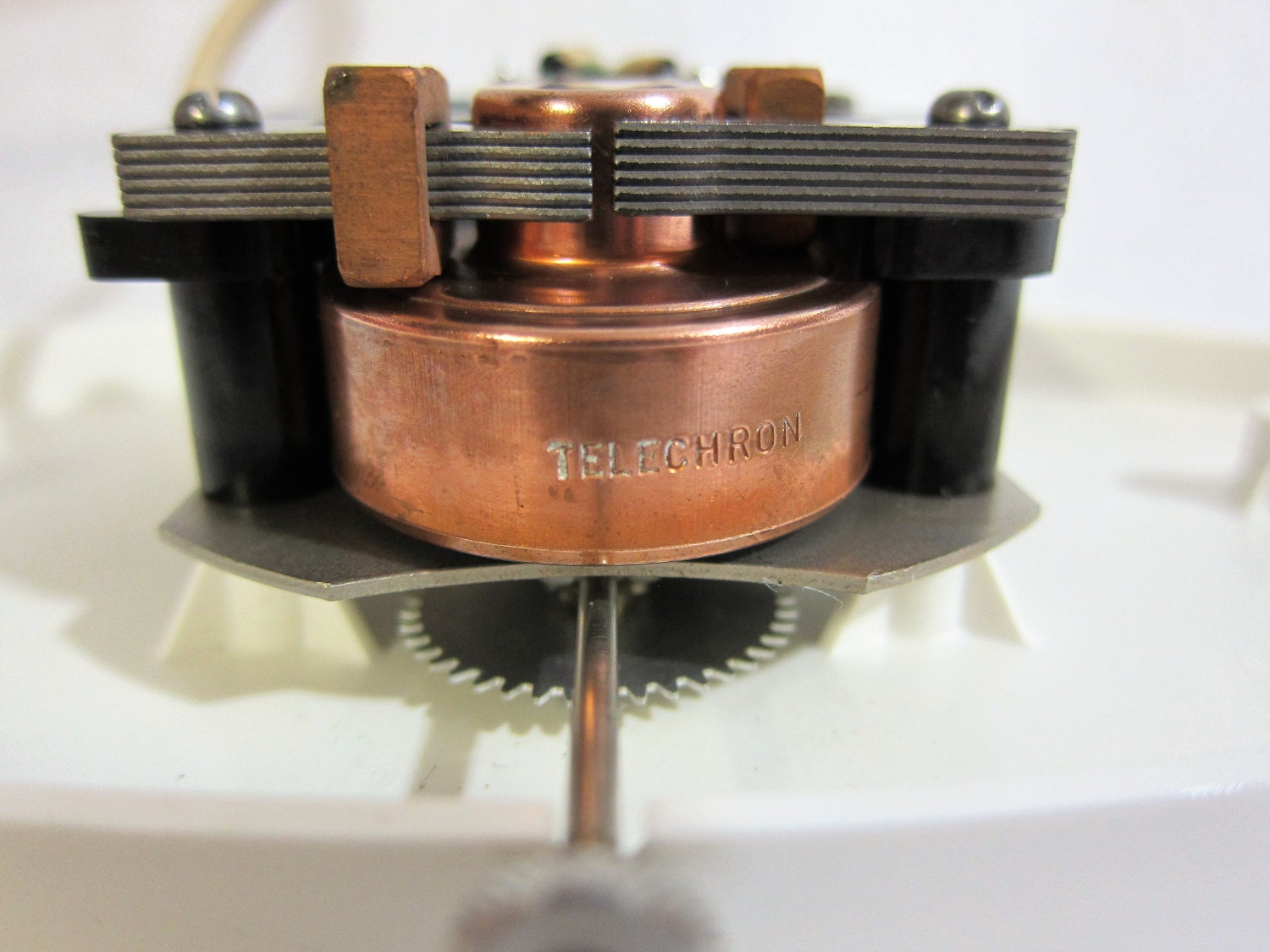

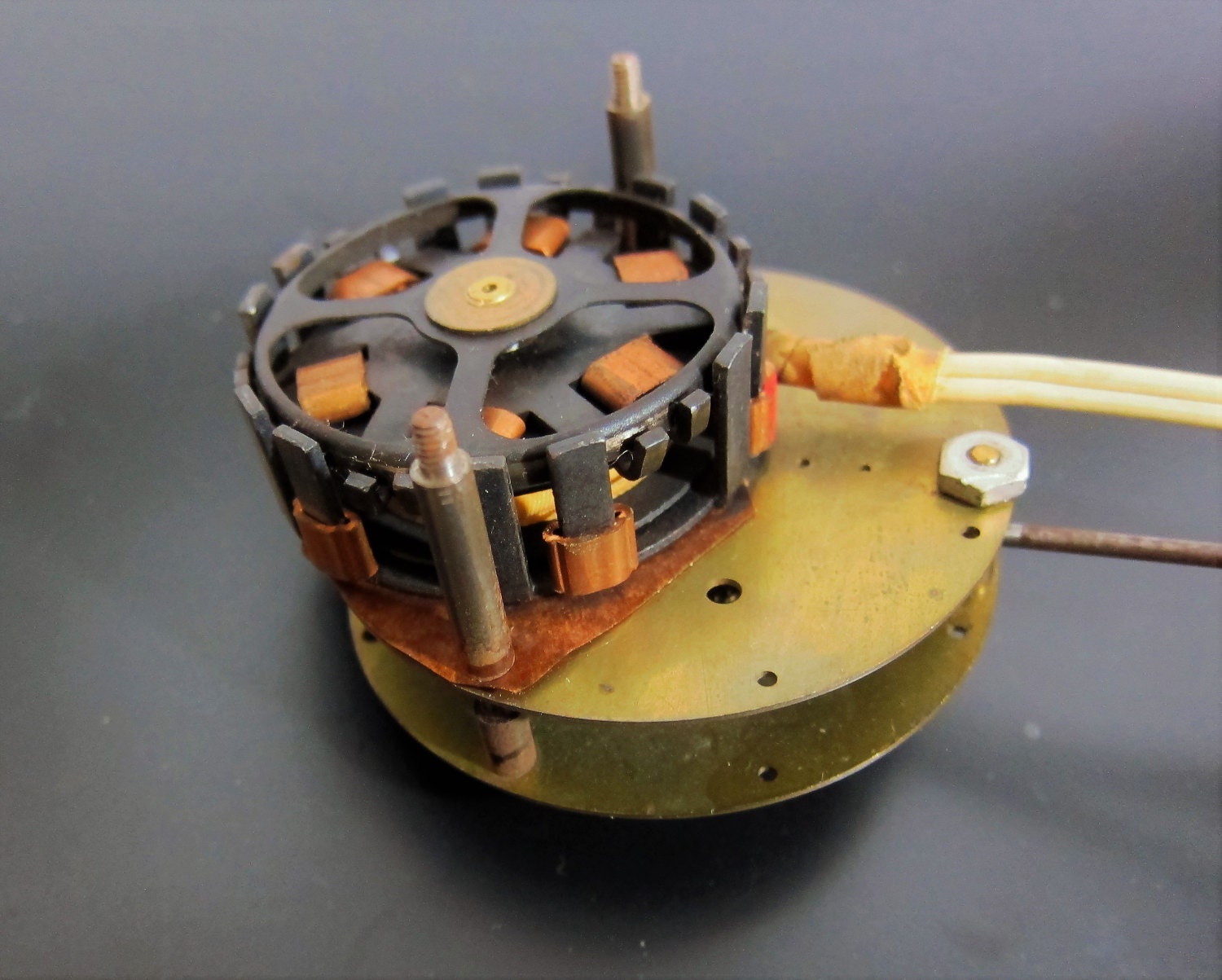

The wonder of electric clocks is that they are regulated by the electrical current that powers them. The lead photo is a Telechron movement with its labeled copper H rotor front and center. The two primary parts of this and other electrics are the coil and the rotor. This power train is somewhat separate from the gear train, which is often very simple. I won't attempt the technical jargon of field coils. It took me years to get the courage to work on electrics, because I'm afraid of electricity. Keeping a healthy fear is a good idea if you intend to use vintage electrics.

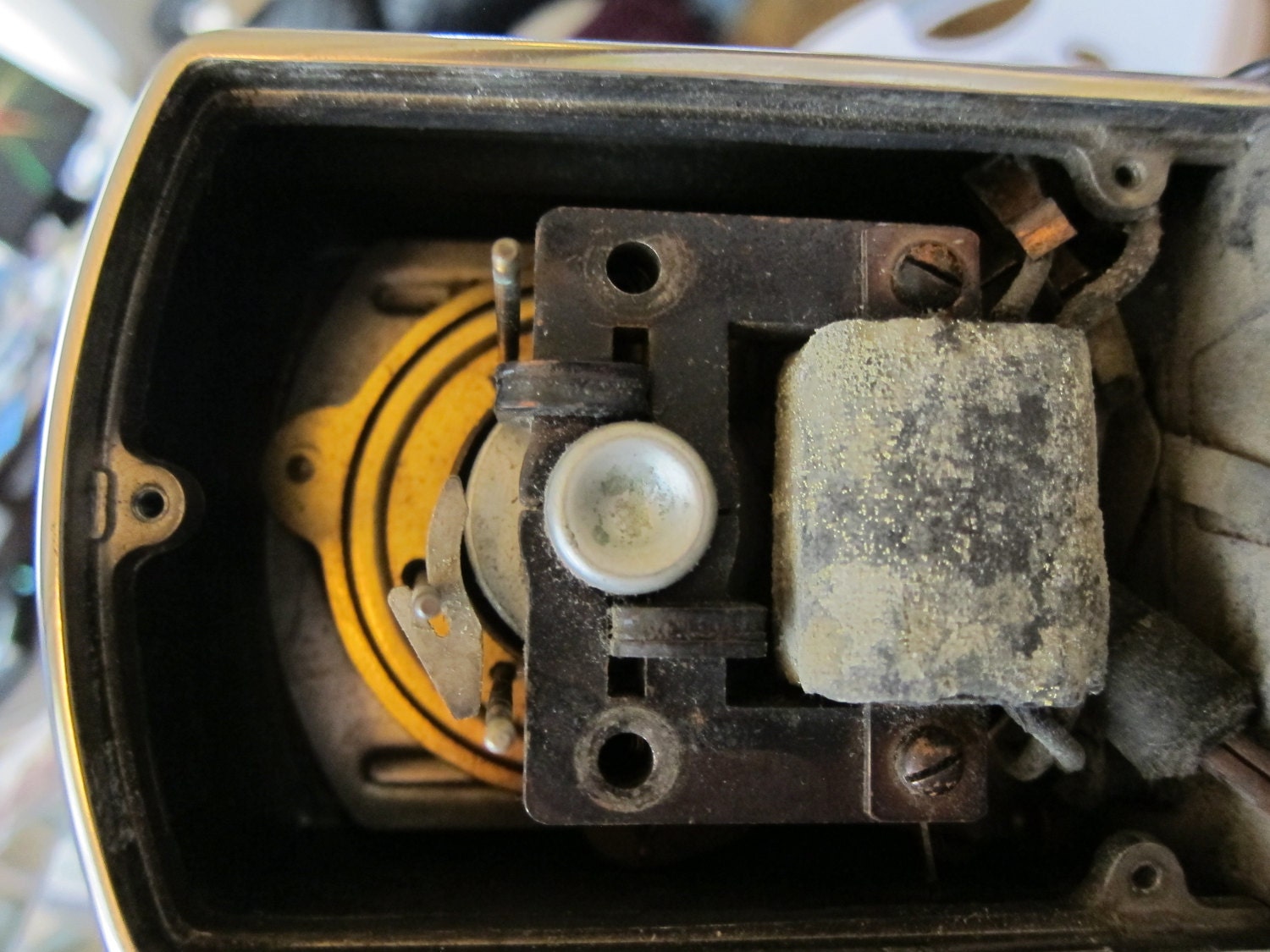

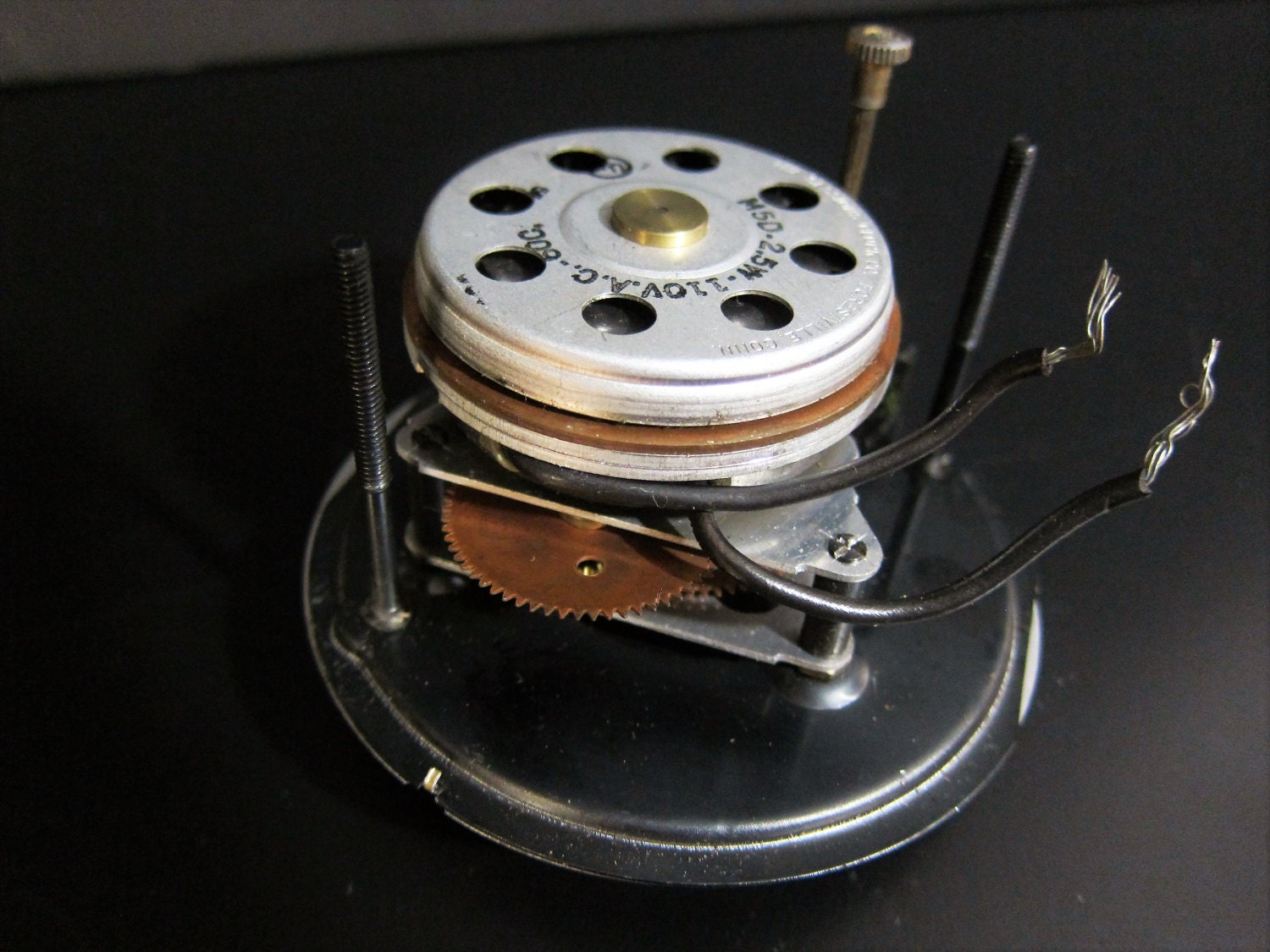

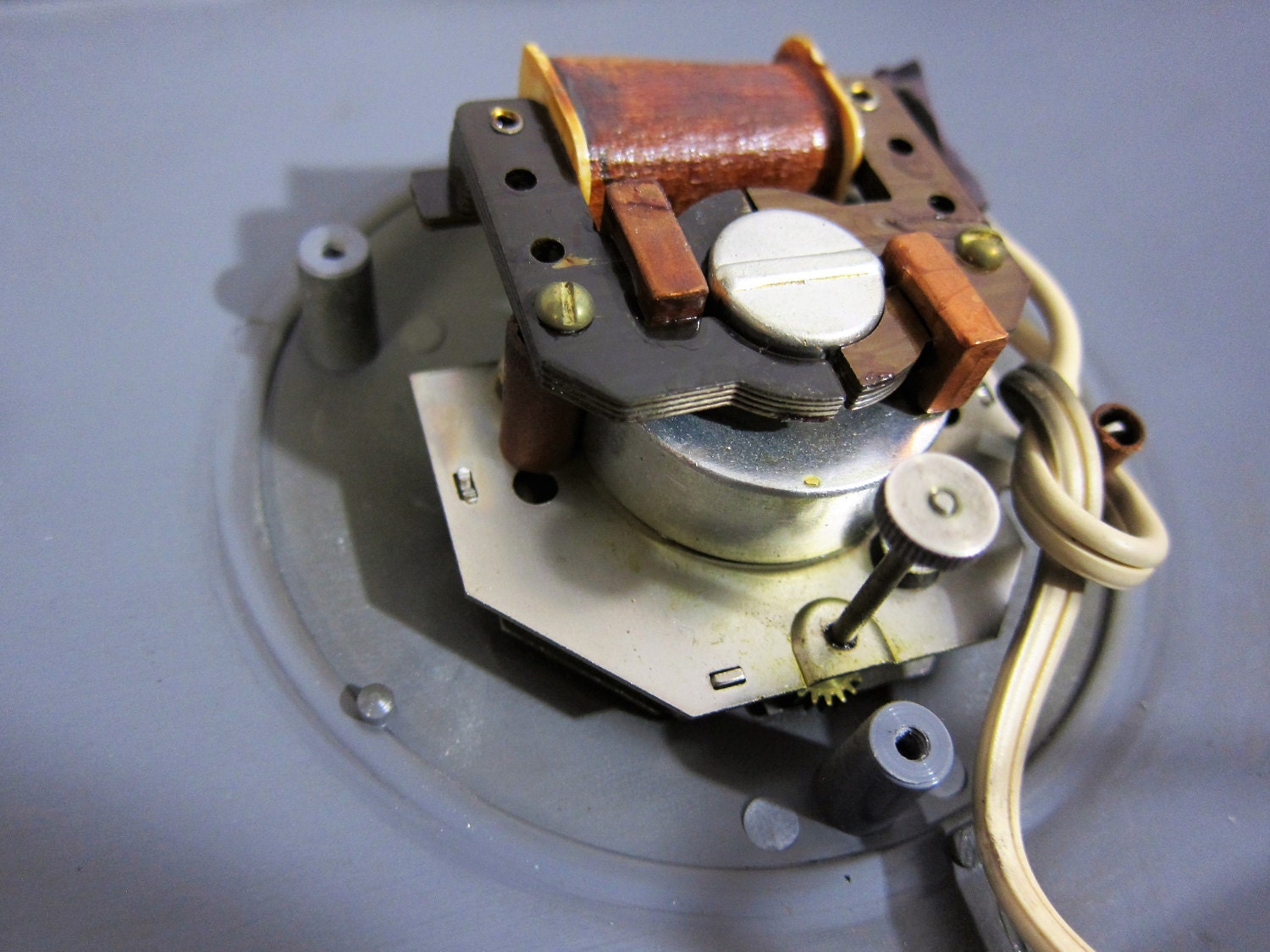

This is an earlier Telechron with a B rotored movement, before cleaning and restoration:

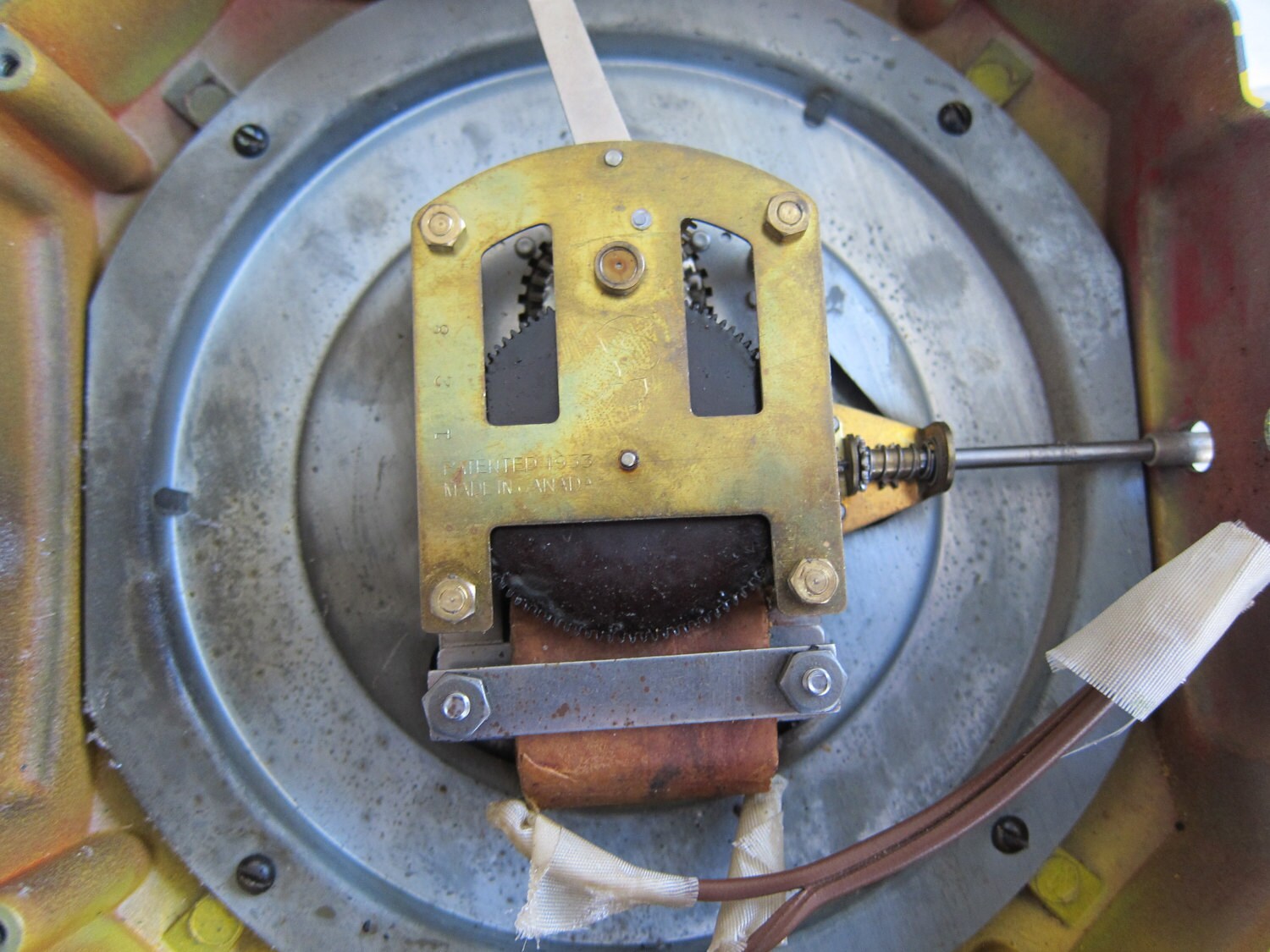

This is one of the first electrics produced by Westclox in the 1930s, called simply "Electric Wall Clock". This is a spin-start motor; it had a lever on the side to push until the rotor started spinning on its own. Later motors were self-starting. This photo was before cleaning and restoration; note the fiberglass tape on the improperly replaced cord. This cord had in fact shorted and burned out the coil; replacements are hard to come by.

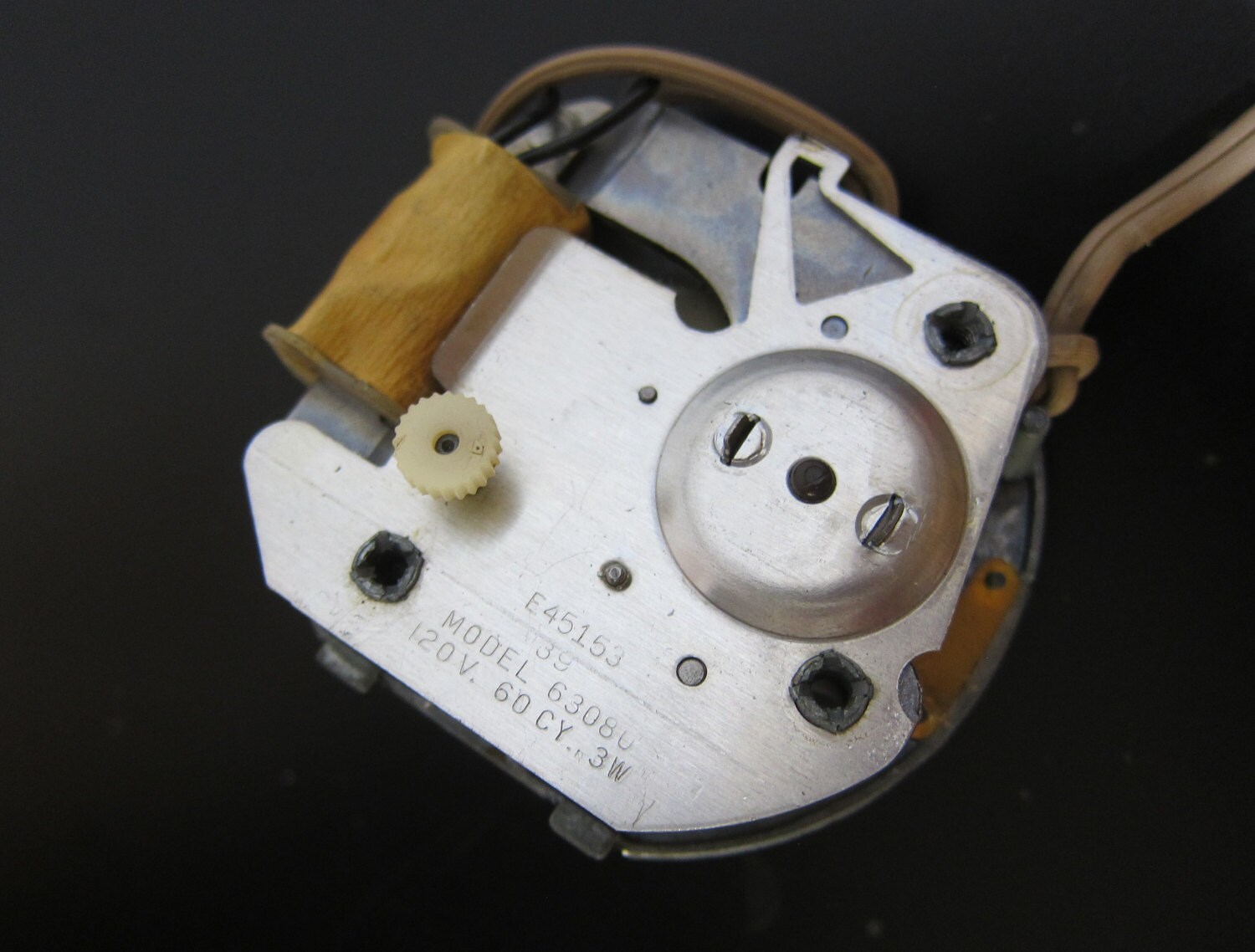

I could write full blog posts just on Westclox motors (and probably will), but will show only this one for now. One important factoid: Note the large brown bakelite wheel in the center of the movement. Telechron and other sealed rotors have the fast moving gears inside the lubricated rotor housing. Westclox and other open rotors have the fast gears out in the open movement. It makes a difference in the noise level when operating the clock.

A brief run-through of electrics from other companies:

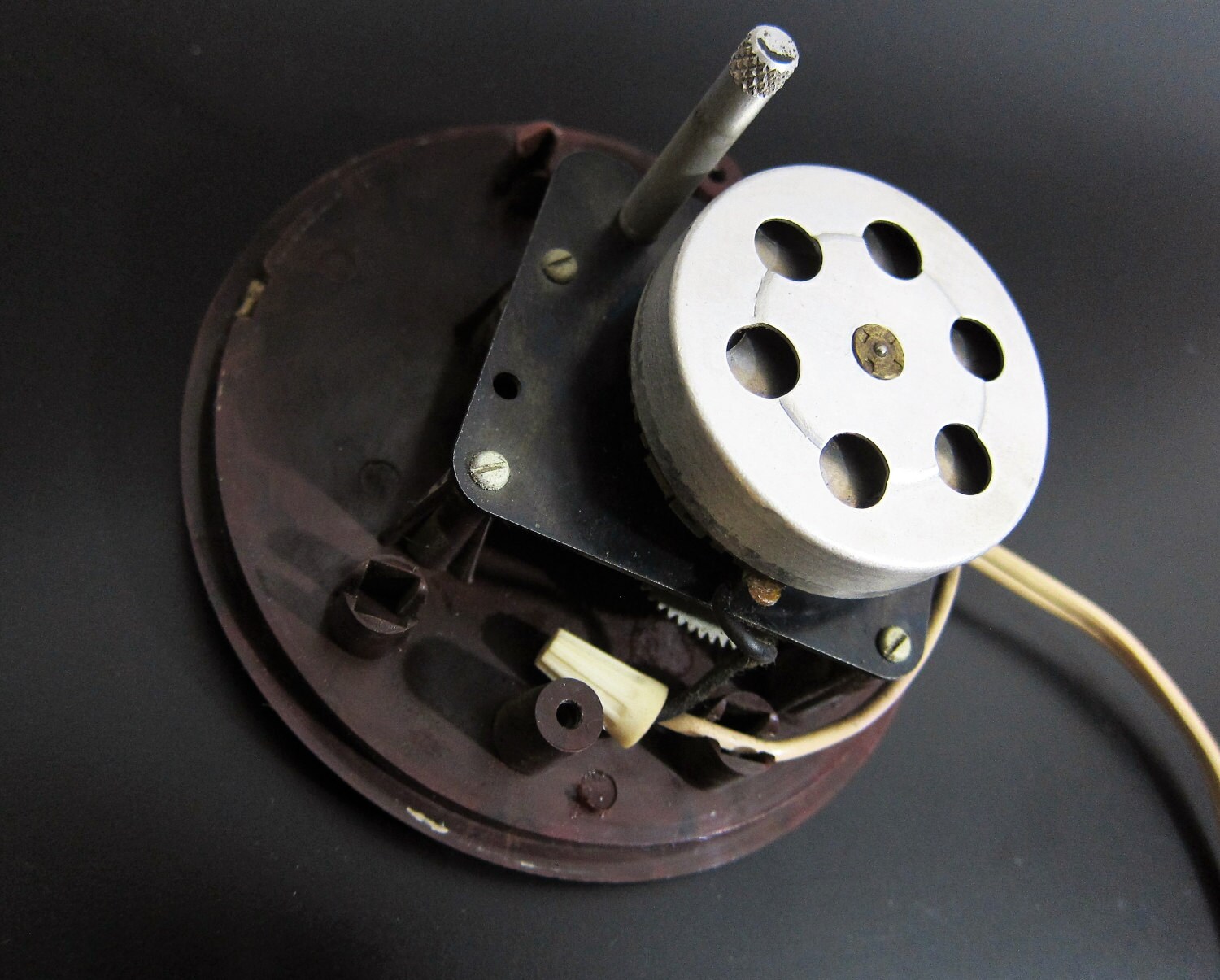

Spartus - with the spinning rotor on top, a very common configuration:

Sessions:

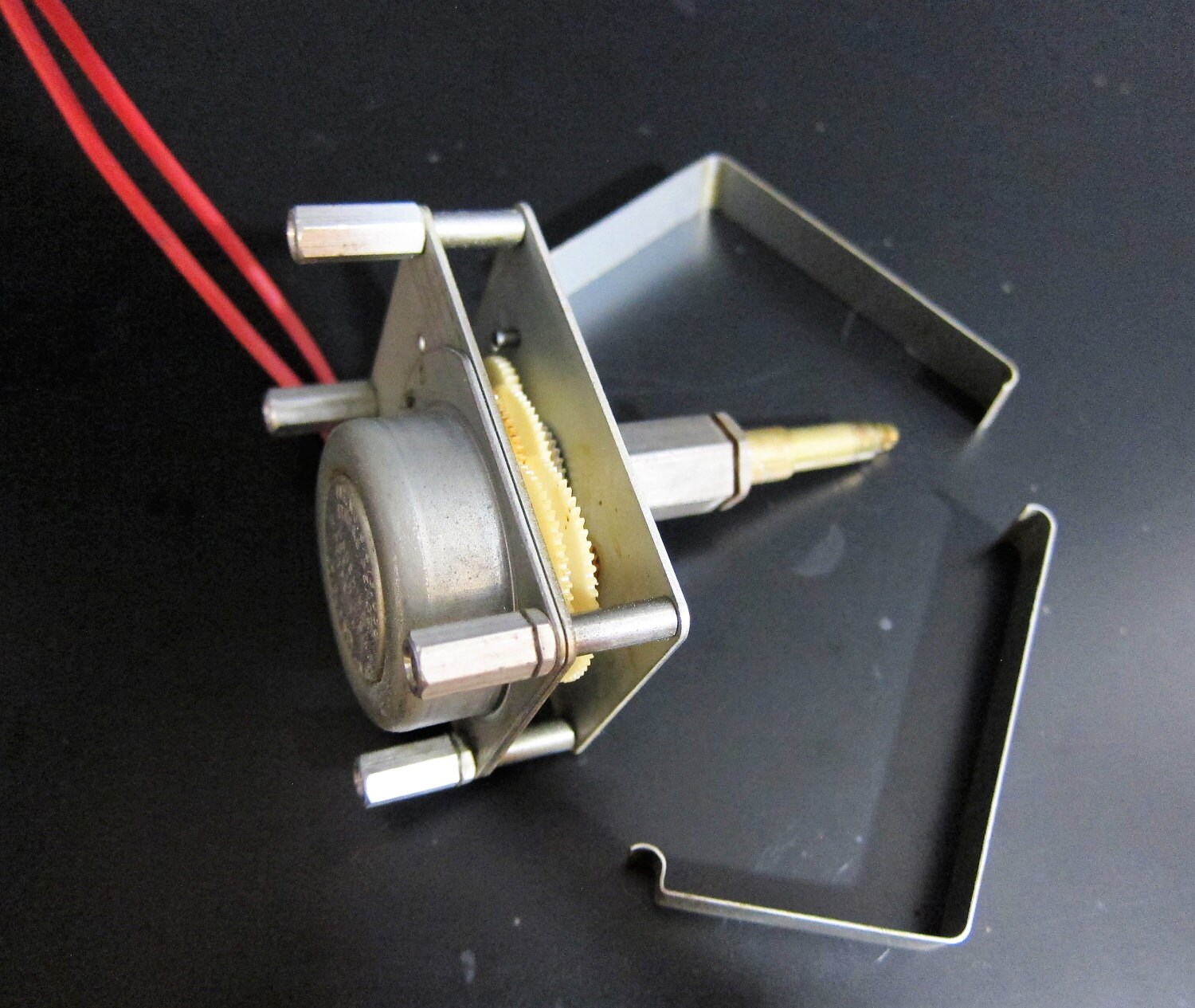

An earlier (1940s-50s) Ingraham:

A later model Ingraham (probably from the McGraw-Edison era):

Poole:

Lanshire, from an advertising clock, a common use for these:

An older Sunbeam, looking very much like a Telechron:

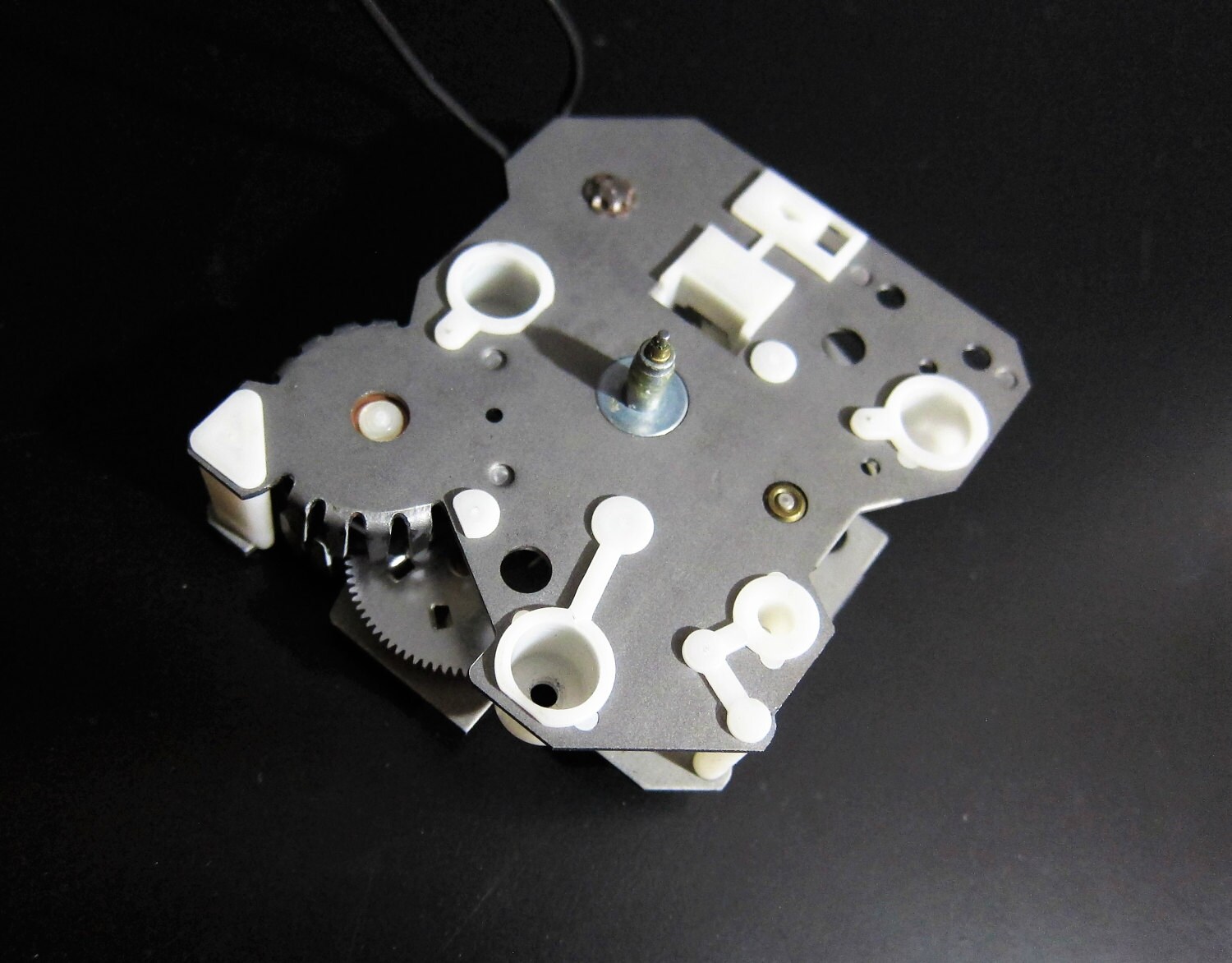

A more recent Sunbeam, with plastic gears and bushings:

The plastic parts go bad on these. The good news is that you can get new parts from a 3D printer and they are easy to repair.

In the more recent decades of vintage electrics, we enter the era of obsolence by design. The movements were staked and riveted, never intended to be disassembled and repaired. Just throw it out and get a new one. I prefer the ones that can be repaired and kept going.

Notes on electrics:

- Wall mains current is dangerous. Keep a healthy fear.

- Noise: No vintage electric clock motor is completely silent, although some are very quiet. They make varying levels of noise, so know your level of tolerance. Normal noises include light rotor spinning whir, or slight noise from gear operation. Louder noises may indicate problems.

- Maintenance, External: Periodically inspect vintage cords and plugs for cracks, brittleness, breakage or other defects. Never pull the cord from the wall; hold the plug end when unplugging. On vintage cords, the flex point where the cord is molded into the plug is a common break point. That's why new plugs have a beefed up flex joint there.

- Maintenance, Internal: Extra important for vintage electrics, which should be serviced more often than mechanical clocks (I recommend every two years, at minimum). Basic service is opening, cleaning and inspecting the clock. Watch for oil leaking from sealed rotors, a sign that the rotor needs to be relubricated. Check the coil: The wrapping should be firm and intact. If not, the motor leads will pull away and the fine copper wire in the coil will break. Check the connections from the cord to the motor leads. Early clocks, other than Telechron, have the cord soldered to the motor leads and sleeved in a thermal coated fabric. The cord is usually knotted close to this connection to keep flexion of the joints to a minimum. Later clocks have the cord attached to the leads with screw-on wire caps, which makes for easy replacement. Telechron is different. The cord is soldered to coil tabs that come directly out of the coil.

- Know your country: I work on American clocks which operate on 115-120 volt 60cycle current. Other countries use different current, and clocks are made specific to those currents. Electric clocks don't travel. Even if you use a voltage converter, the difference in cycles or hertz will cause your clock to run fast or slow. That's why I don't automatically ship electric clocks outside the U.S. or Canada.