There are three primary types of vintage (pre-quartz or pure electronic) clock movements: Spring driven; electric; and hybrid (I have obviously passed over older types of movements such as pendulum driven). This post is about spring-driven movements, also known as keywound or mechanical. These have the gear train powered by a coiled strip of spring steel, and the timing is regulated by a fine hairspring on a balance wheel.

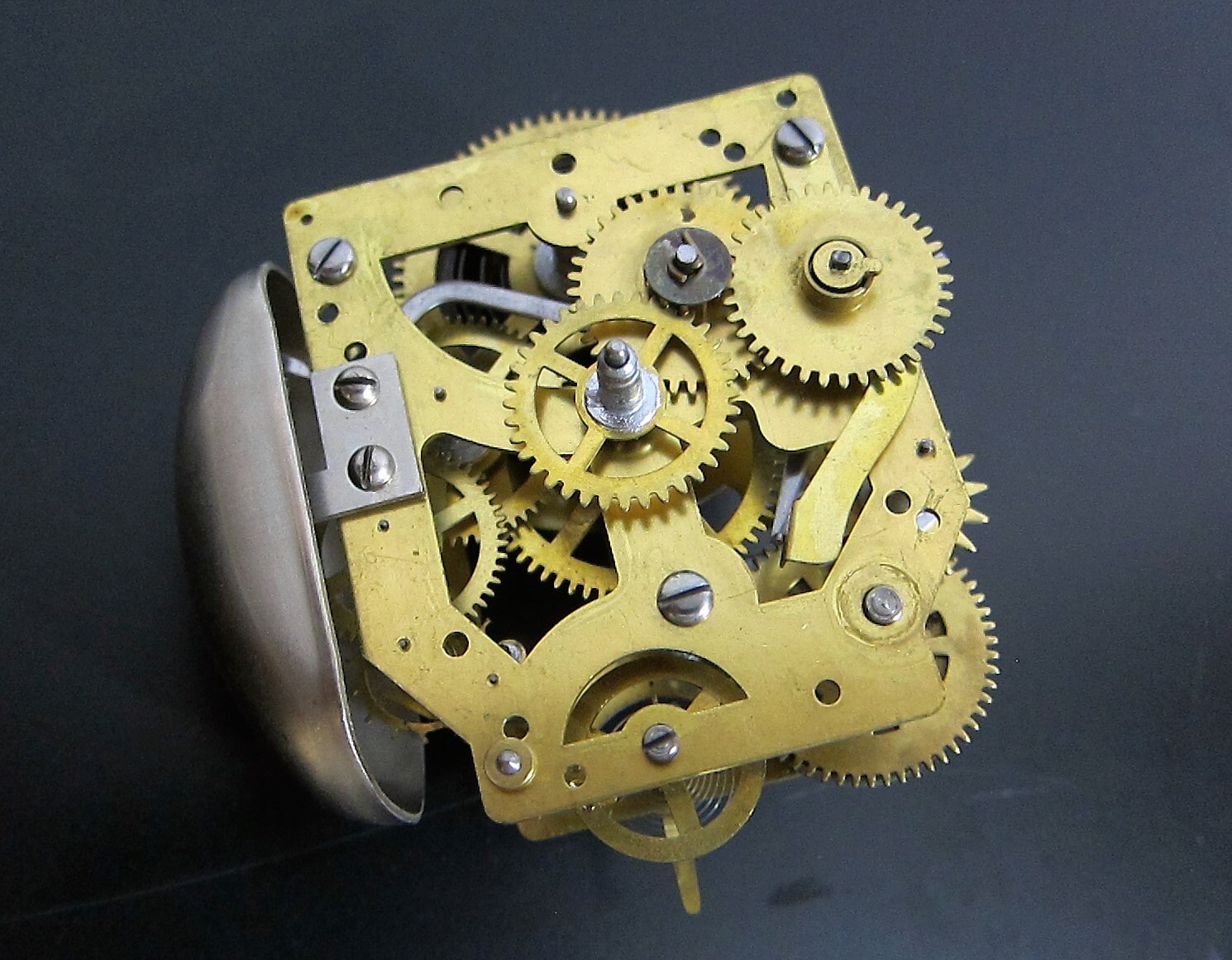

The movement in the lead photo is almost a work of art - or truly is one, if you consider industrial design an art (and many clock lovers do). That one is from a 1930s Westclox Sleep-Meter alarm clock.

The pre-war 1930s were a great era of industrial design, in line with the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne design movements and a real sense of pride in the manufacture of quality goods. This next beauty, also 1930s, is a Westclox LaSalle alarm clock (sometimes called the "Microphone" clock):

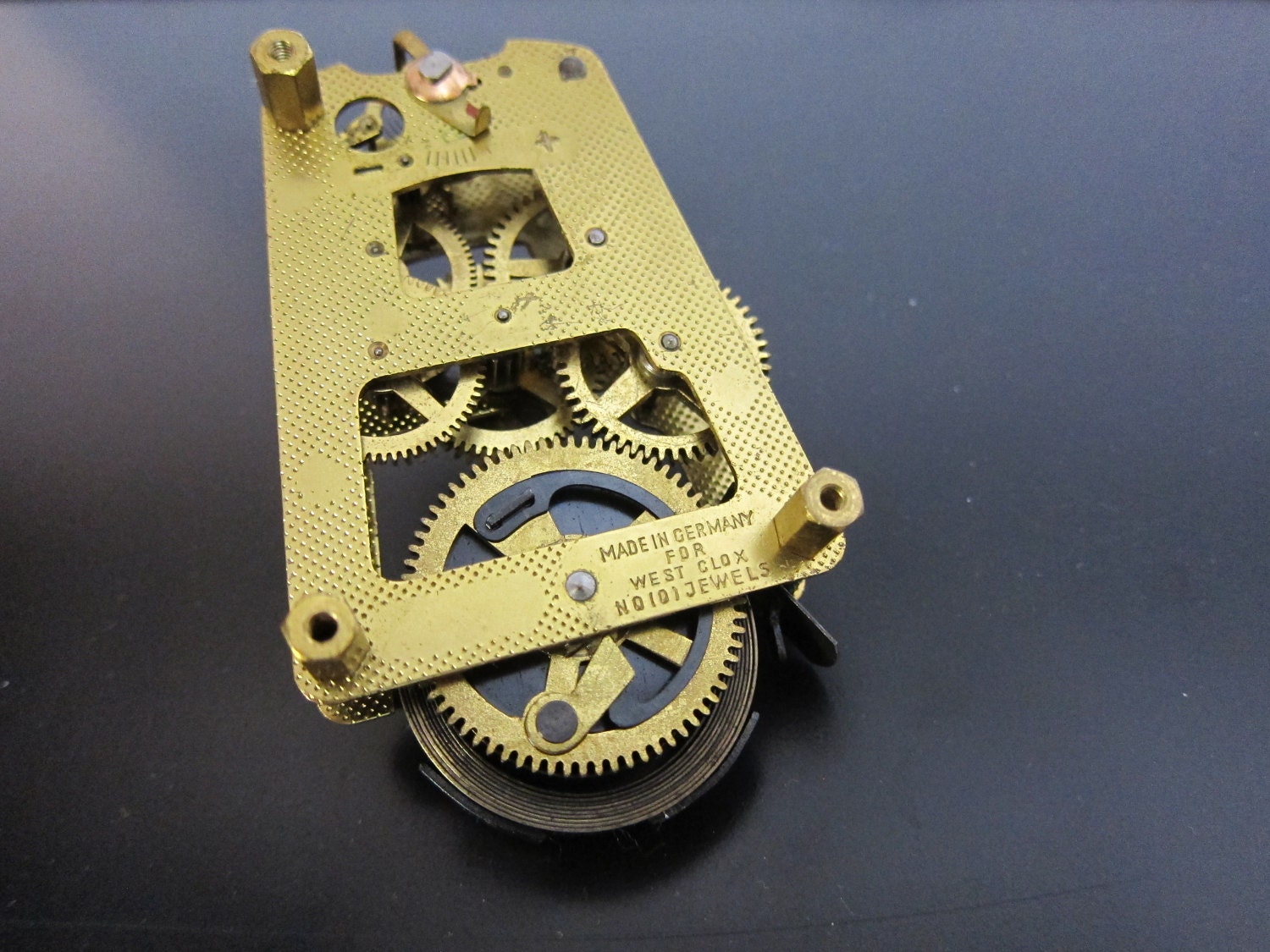

Post-war, things changed and manufacturing bases shifted. Some of the better clock movements were being made in Germany. American and other clock companies sometimes used German movements in their midcentury clocks. This is an 8-day movement for a Westclox Granby, a large starbust clock. The 8-day springs are very powerful and can be scary to work with; you have to use the proper tools (spring winder and arbors) and take safety measures.

Here is another 8-day German import movement. This one is from a Westwood Chadwick starburst clock, but the identical movement was used for many different clocks.

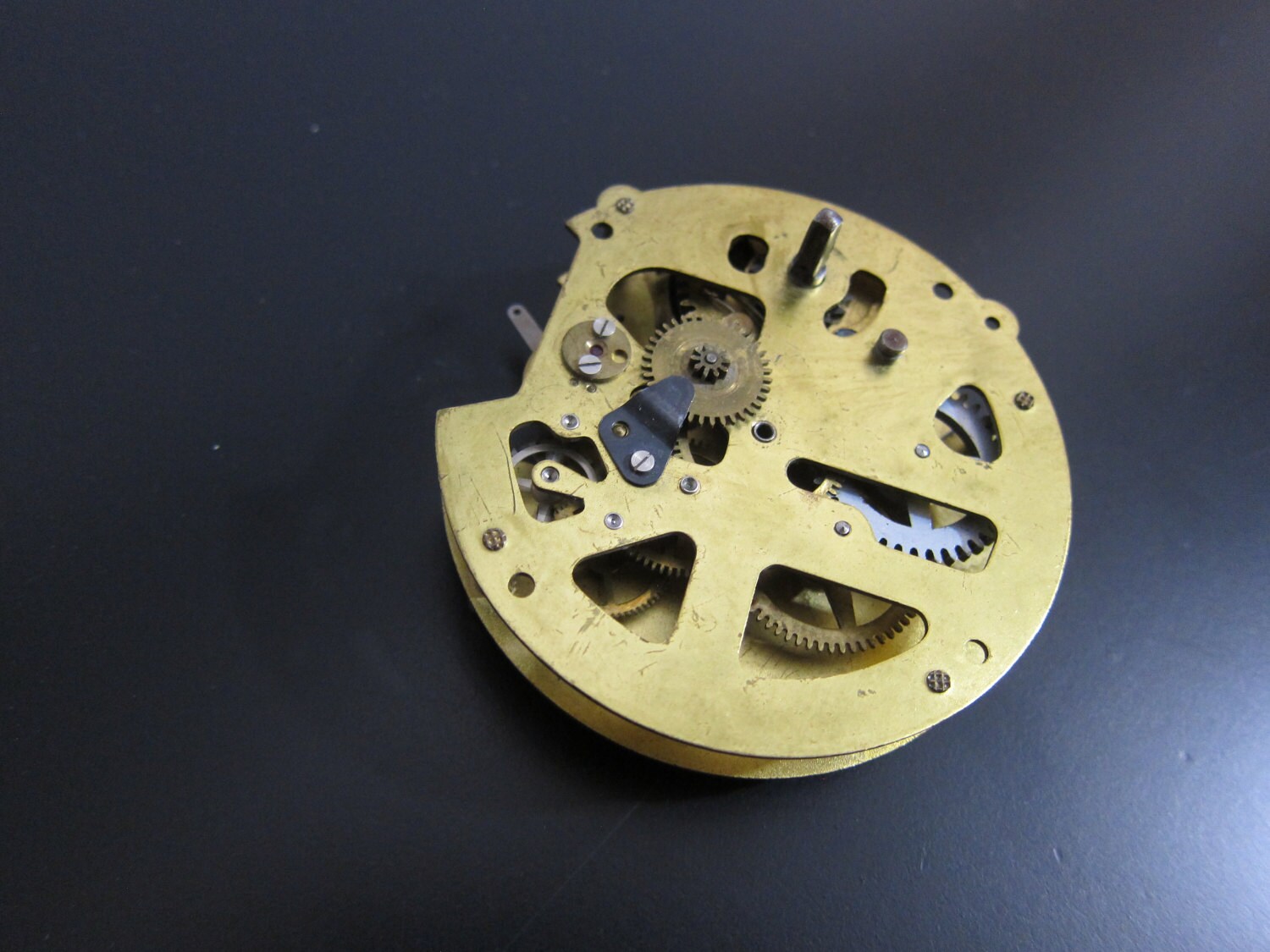

German brands gained acceptance and a reputation for high quality in their own right. Here is a movement from a Kienzle wall clock, a sought after brand that can fetch high prices.

The Blessing-werke German clock factory came to dominate the market for imported clock movements. Many brands - Elgin, Welby, Blessing, Linden, and others - all had similar clocks that used identical Blessing movements. Here is the alarm version of the movement I see the most often:

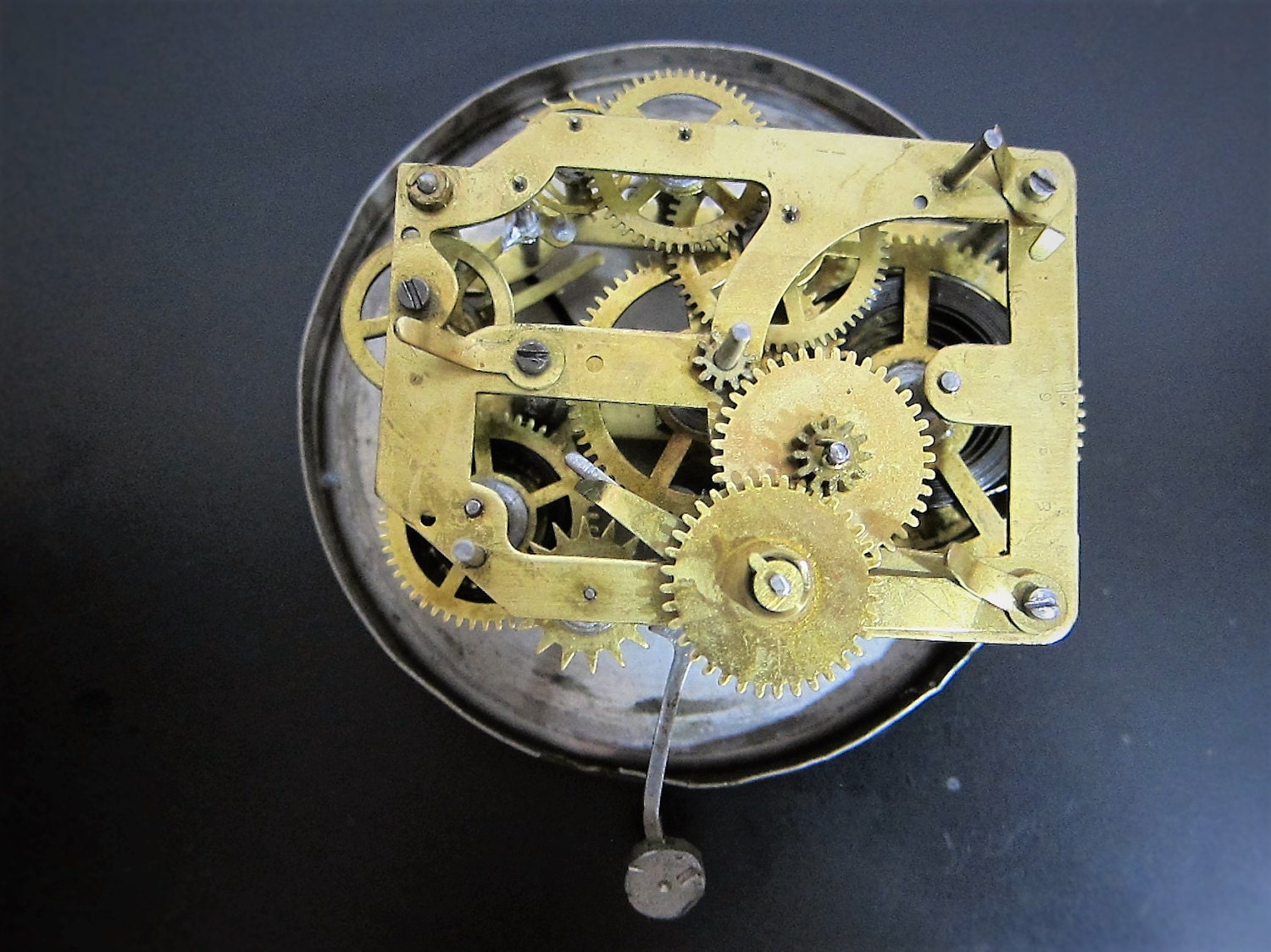

That one was from a miniature twin bell alarm. Here is the identical movement, disassembled along with the parts of the larger Snoopy alarm clock it came from:

The last one I'll show here is a 1906 Westclox movement, 110 years old. The history of Westclox is fascinating as an overview of the history of United States manufacturing and industrial design. I can get emotional thinking about it. For more information I recommend the excellent website at clockhistory.com.

A few ending notes on care and use of vintage spring driven clocks:

- Noise: These are the classic, ticking clock. They make noise. Some people who have grown up with only nearly silent quartz or electronic timekeepers find the noise obtrusive. Some of us find the noise comforting, like the puppy quieted by a ticking clock placed in its bed to sound like its mothers heartbeat. Then there is my poor son, who had to listen to the sixty or so clocks I would wind every day for years. He won't tolerate a ticking clock.

- Operation: It may seem obvious, but these have to be wound, with an attached or an inserted key, either daily or weekly, depending on the spring type. Metal springs change with temperature and environmental conditions, and with age. Spring driven clocks usually have a fast-slow adjustment on the hairspring balance wheel which is sometimes necessary to use.

- Maintenance: Mechanical clocks use a fine grade clock oil, where the pivots go through the movement plates in particular. They need to be disassembled and cleaned periodically. If not, the oil collects dirt around the pivots, whose continual action wears the pivot holes in the movement plates, until the hole is no longer round. There is then uneven movement to the gear, which impacts the function of the clock. Repair requires bushings in the movement plate, which is no fun and most clocks don't merit such a repair. Much better to keep them clean in the first place.

- It doesn't pay to bypass proper maintenance. Spraying WD-40 in the clock is a huge no-no. I have also seen clocks with large accumulations of other oils like automotive motor oil. These will accelerate the need for more costly repairs or demise of the clock.

- When buying a vintage clock, if you haven't seen the inside, there may be surprises. Insects, dust bunnies, rust; broken or missing parts or bad repairs; buyer beware.